The Photograph Collection

The photographic library is a collection of old photographs belonging to the Dominicans of Jerusalem and held by the priory of St Stephen Protomartyr in Jerusalem, the seat of the French School of Scripture and Biblical Archaeology. In law the collection is the property of the Priory and the Dominicans of Jerusalem, and so ultimately of the Order of Preachers. In 1890 the young School included in its annual programme of studies the discovery of the lands of the Bible by means of regular excursions in which the students mingled with their teachers. The systematic visiting of the terrain naturally began with Jerusalem, which was the object of careful study year by year, and then all the land of the Bible in expanding circles. Frontiers were less constraining than they are today, and the “Bible caravan”, as it was nicknamed, was able to explore the Negev to the south and eventually Mount Sinai just as it did Transjordan, Hauran, the country about Damascus and Palmyra. The journey was made on horseback or by camel. These excursions took the place of lectures. The Dominican professors introduced the students to the study of epigraphy, to archaeology and historical geography, indeed to geology too. The caravan was exultant when it chanced on an unrecorded Roman milliary column, a stele which a fallah might come to show them, a tomb in the flank of a cliff, or a fragment of mosaic. It offered the opportunity for an enthusiastic production of estampages, measurings, drawings and concise descriptions. And of course for photographs.

This was the context in which the School’s practice of photography developed. As far as technique was concerned it was a matter of the self-taught, but the choice of themes was the affair of experienced teachers who were experts in their respective disciplines. Hence the particular look of these photographs, taken by or for men of learning and not, as was often the case at that period, intended as more or less naive or romantic illustrations of the sites and events of sacred history.

The photographs are there to witness to the discovery of this or that object, to the content of the matter being studied, the accurate deciphering of an epigraph, etc. In a slightly positivist perspective the photo could then be seen as an objective proof to complete the description, the design. It was held to be just as precious as a print, one more indubitable proof. The artistic dimension emerges almost unintentionally. The powers of observation of the friar who takes the photograph, his general culture including his knowledge of iconography, and his sensibility count for a great deal.

Paradoxically, in essence the collection consists of thousands of glass plates, 12,500 negatives and another 4,000 positives intended for projection, plus 33 autochromes (early colour photographs). There are no sepia prints on albuminous paper as might have been expected (1). It is astonishing that we only have a few tens of prints from the period (‘vintage’ prints). They are sepia contacts from a glass negative where the glass has disappeared and only the paper print of the image remains. The small number of paper prints illustrates a peculiarity of the Dominican collection: at that period it was not viewed as a collection of photographs for the public to see but as a scientific tool for internal use. Amongst the brethren, in the course of conversation, it was a simple matter to find this or that series of negative plates, stored in the rooms of the cameramen. Originally the building did not include a library of photographs; the plates stayed in the cells of the brothers depending on the subject each had worked on. When they had died it was decided to set up a central archive. Each photographer among the religious had a good memory of his own photographic archive and had no need of an album of albuminous prints. Systematic making of contact prints would no doubt have been too costly. The key to the interpretation of the collection is to be found in their publications, realized or projected. The photographs witness to the researches of the Dominicans, illustrating monographs or articles of the scientific periodical of the house, the Revue Biblique that had been founded in 1892, only two years after the modest yet daring launching of the School itself. The articles were embellished with photographs, reproductions of estampages, and, obviously, inventories, drawings, sketches, made by the authors or delegated by them to the member who was the most gifted with pencil and pen, Hugues Vincent. Vincent made the inventories, drawings, stratigraphic sections, and also the estampages. Everyone knew how to take estampages. The photographers were Séjourné, then Carrière, Jaussen and Savignac in particular, Savignac in his old age (2), Tonneau and then from 1935-1936 Pierre Benoit and Roland de Vaux.

The themes that formed the subjects the monographs, realised or planned, are reflected in the contents of the collection of old photographs. The magnificent books in a large format which we mention are the ripe fruit of researches by authors working in pairs, H. Vincent and F.M. Abel on one hand, A. Jaussen and R. Savignac on the other. We shall refer to these works as we follow the chronological development of their activity. We owe the larger part of the production of photographs of the School to the two pairs, directly in the case of Jaussen and Savignac who were themselves photographers, and indirectly with Vincent and Abel, who were neither of them photographers and ordered particular negatives for the works they had in preparation. Some themes received special treatment: a history of the development of the wall of Jerusalem, the monuments of Haram es Sharif, finally the esplanade of the Mosques and the ornamented capitals that served as chronological markers. A comparison with the photographic collection of the Fathers of the Assumption of Notre Dame de France at Jerusalem points a contrast with the surprising feature of the School, the near absence of prints on paper. At the School the photos are too austere, too “scientific”, to attract a wide public and pilgrims. So it is that the collection of the School has remained private. Only members of the universities could have a glimpse of them by means of the publications.

Not long ago our original collection began to expand. First of all in 1994 we received 1,603 glass plates of all formats, including impressive 24×30 cm examples, from the Assumptionist Fathers of Notre Dame (reference NDF), taken between 1888 and around 1930 in the Holy Land and neighbouring territories. By its period and the spirit of its conception, the NDF collection is the nearest to our own. A few years later the contemporary Assumptionists of St Peter in Galicantu authorised us to digitise 302 paper prints from the large albums of the NDF which no longer had their original glass plates, albums which St Peter in Galicantu had fortunately kept after the sale of Notre Dame. We have been allowed to digitise the album of small paper prints of the Schmidt School, the former German Paulus Hospiz (139 photographs, unpublished, datable between 1907 and 1911. There came to us the Spanish gift of 708 unpublished originals (paper and a few negatives) from the Dominican M. Ferrero Gutierrez, made when he was a student at the School between July 1929 and June 1931. Ferrero took part in the study-journeys of the School, hence the presence of photos of Cyprus, Egypt, Syria, the Transjordan, besides Palestine properly so called. These negatives, made in the spirit of the School, bring our collection happily to completion at the time when the pioneers Jaussen and Savignon were growing old. In 2008 we asked our confrères the White Fathers of St. Anne in the old town of Jerusalem for permission to digitise their 701 glass plates. They are mostly unpublished, and the oldest of them date from before the foundation of our own School. They cover the period from about 1875 to 1939. To these plates we have added about 872 photos on paper, old ones, belonging to the same White Fathers, for digitisation. We have included 366 prints from the album of the Italian Salesian Fathers of Beit Jimal (from 1930 to 1940). The Jesuits of the Pontifical Biblical Institute of Jerusalem gave us permission to digitise 1,740 photos, negatives, on glass and acetate, sometimes on paper, for the most part from the 1930s (3). At present we are engaged on the archives on glass of the Albright Institute which document the American excavations of the 1930s. From our own family we have received some large format prints on paper of Syria and Jerusalem taken between 1922 and 1925. Some coloured slides have been handed on to us by former students of the years 1960-1970, and finally some have come from certain families of pilgrims from those years. With the passage of time, any photo that predates the recent local wars becomes a precious document. Some Bonfils have been given or lent us for digitisation (4). The series digitised has reached 285 Bonfils.

The first negatives are those of the founder, Père Lagrange, an amateur photographer who did not follow up his early efforts. He had taken photographs at the time of his first journey to Jerusalem, during a stop in Egypt where his ship had called – this was in the Spring of 1890. From his short journey “beyond the Jordan” there remain the first negatives of the collection on Jordan, belonging to the same year. An exposure from a decade that was poor in negatives corresponds to the period of formation of some very young friars who arrived between 1890 and 1892, Lagrange’s first pupils who were yet to be introduced to photography. A few photographs from the years 1896-1898 are the oldest and they were taken by Séjourné. Here also is the famous negative of Petra, taken in October 1896, in which a long makeshift ladder is to be seen leaning against the façade of the Nabatean tomb of Tourmaline. Vincent is climbing it in order to take the first estampage ever made of the great funerary inscription engraved on its pediment. The team of the founders is there surrounding Lagrange, the young Jaussen, Savignac, Vincent, Abel, etc (5).

From 1900 onwards, with a peak between 1905 and 1907, the young men took up photography seriously, in particular the two friars who for almost a lifetime were to be the principal photographers of the School, Raphaël Salignac (1874-1952) and Antoninus Jaussen (1871-1962). Jaussen’s first photos are perhaps those of the estampages he took at Damascus in 1897 in the course of the School’s study-journey (6). The excursions were sometimes commissioned by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, like that made to Petra in 1896, which gave rise to a breaking-up of the archive: all the glass plates remained at Jerusalem whilst a part if not the whole of the estampages were ceded to the Institut de France. This was also the case for the expedition to the Negev in 1904, when the Académie had requested a study of the Nabatean inscriptions of ‘Abdeh/’Abodah. A team composed of Jaussen, Savignac and Vincent made three articles out of it for the Revue Biblique (7). We may note how swiftly they were published. It was also in 1904 that Jaussen visited Jebel Druze and so began his career as an ethnographer. Ethnography was of most importance in the researches of Jaussen and the occasion for his series of original negatives, particularly those linked with his role as researcher and teacher of Semitic epigraphy. His ethnography, besides articles, resulted in two volumes which remain first in their field and a source of photographs still in demand today. The first is Coutumes des Arabes au Pays de Moab, Paris 1908, reprinted by LULU Press 2018, a work on the life of the Bedouin of the Transjordan with its celebrated appendix on the history of the Christian tribe of the ‘Azeizat which at that time had migrated from Kerak to Madaba. Jaussen had personally interviewed them. The second work of ethnography is Coutumes Palestiniennes, Naplouse et son district (Paris 1927). The urban surveys he made form a pendant to the customs of the nomads and belong to a very different context. The stereoscopic views of the soukh of Nablus are of great value as they were taken before the earthquake of 1927.

In the wake of the epigraphical and archaeological expeditions of the School which provided an opportunity for a number of photographic negatives to be taken, the outstanding ones are Sinai in March 1906, the Negev, and lastly Petra (8) reached by travelling south from the Dead Sea. Savignac led the caravan as far as the Negev where he found Jaussen who had arrived from elsewhere to negotiate their passage with the unruly tribesmen there. Jaussen took ethnographic notes and made photographs during the whole journey, and naturally Savignac took his pictures too. Then the pair took up the great matter of the Hijaz, three journeys in 1907, 1909 and 1910, and the book Mission en Arabie, the title of a five-volume work plus one of illustrations (9). The objective as requested by the Académie des Inscriptions was the exploration of the Nabatean sites of Medain Saleh and al’-Ula. The publication remains a mine of photographs: it goes beyond the scope of the famous epic journey to the Hijaz to include two volumes on the castles of the Jordanian desert, notably with the rarest of pictures of the Ummayyad frescoes of Quseir ‘Amra, as they were before the rash restorations attempted later. The importance of the photographs taken in Arabia, if one adds those of Savignac taken during the 1914-1918 war, merited the exhibition which we have twice presented in Saudi Arabia, “Hijaz 1907-1917” (Riyadh in April 2000 and Cheddar in October 2000) in partnership with the Institut du Monde Arabe (10).

Cruising on the Dead Sea also gave great opportunities for photographs. The first to be planned was Jaussen’s idea (11). He took twenty people from Jerusalem, students and teachers, on the first motor boat to be launched on the Dead Sea, at the time of the Christmas holidays from December 28th 1908 to January 7th 1909. Savignac took a number of pictures, as did the others. We have recently inherited 296 glass plates from a Belgian student who took part in the cruise (12). In 1912 Vincent and Abel finished their monograph on the basilica of Bethlehem, illustrated with pictures taken by Savignac and Carrière (13). Just before the Great War, Jaussen and Savignac led two expeditions to Palmyra with an abundant harvest of photographs, some of which were the first ever taken of their subjects.

The 14-18 war was the unexpected occasion for a series of original photographs made by Savignac. As an information officer of the French Navy working as a translator from Arabic, he teamed up with Jaussen, his senior officer in the same department. They were based in Port Said and saw a lot of their fellow-translator the young Englishman T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia). Taking advantage of voyages aboard warships, Savignac took magnificent phonographs on the island of Rouad (Syria), the isle of Castelorizo, and also the coast of Hijaz, Al Wajh, Yanbu’ and Cheddar, the Suez Canal, Port Said, etc.

Thanks to the relative ease of access to the Muslim sanctuaries of Palestine at the beginning of the British Mandate, the Dominicans were able to photograph the Haram of Hebron with a view to the large monograph (14) published by Vincent and Abel in 1923. It was probably the same favourable circumstance of easy access to the Muslim holy places that allowed Jaussen to make his series of stereoscopic views of the Dome of the Rock and its mosaics. A little later Vincent and Abel published with the same editor another monograph, Emmaus, with many photographs to illustrate the clearing of the ruins (15).

The Dominican Fathers were not in the habit of signing their photos or dating them, as they were intended only for the publications that were under way. The resulting puzzles are for today’s archivist to sort out. The answer lies in the publications, case by case. The date of printing at least gives the picture a terminus ante quem. It sometimes happens that the work itself mentions the circumstances in which it was taken, with date and place, particularly when an expedition was to faraway places in exceptional conditions (16). By contrast, with composite works bringing together material from different periods it is not possible to date each one individually (17).

(1) In consequence the collection has no financial value. Glass plates are not in demand. Only prints taken in the period are available in the saleroom.

(2) Antonin Jaussen gave up photography after he was charged, after 1930, with the new foundation, the Cairo house, the daughter-house of the School. His last photographs show the construction of the Cairo building.

(3) In this batch there are a hundred plates from January 1914: the excavations at Elephantine, Upper Egypt; and the negatives from the dig at Teleilat el Ghassul (Dead Sea, bank of the Jordan).

(4) Similarly 44 fine copies presented by Mlle Marie-Arnelle Beaulieu of Jerusalem.

(5) See the picturesque story in Revue Biblique 6, 1897, pp. 228-30. The long estampage, on 34 sheets of paper, was presented to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres.

(6) See Revue Biblique 6, 1897, pp. 592-597, the first of his scientific articles, published when he was 26.

(7) RB 15, 1906, pp. 403-424; RB 14, 1905, pp. 74-89. and pp. 235-257. The Académie published the report by Père Séjourné in CRAIBL 1904, pp. 279-305.

(8) RB 15, 1906, pp. 443-464. They sent out to go by way of Ain Qedeis following the itinerary of Père Lagrange in 1896.

(9) Mission archéologique en Arabie I – De Jérusalem au Hedjaz. Medain-Saleh, Paris, E. Leroux, 1909. Followed by Mission archéologique en Arabie II – El ‘Ela, d’Hégra à Teima. Harrah de Tebouk, Paris, P; Geuthner, 1914 (it appeared in 1920). Finally, Mission en Arabie III, Les châteaux arabes de Queseir ‘Amra, Harâneh et Tuba. Texte et 21 fig.; Atlas et LVII planches, Paris, P; Geuthner, 1922.

(10) In December 2003 we also mounted a second exhibition in Arabia, at Riyad: Al-Quds al-Sharif, also from IMA Paris.

(11) It became the subject of an exhibition shown at Jerusalem and Amman in 1997, with a printed catalogue, Périple de la Mer Morte 1908-1909 (Journeys on the Dead Sea 1908-1909) Ramallah-Jerusalem, 1997.

(12) He was M. Jules Prickarts who afterwards became a professor of the faculty at Liège. His grandson Charles Prickarts presented us with the original glass plates from 1908-1909.

(13) Bethléem, le sanctuaire de la Nativité, by L.-H. Vincent and F.-M. Abel, Lecoffre, Paris 1914 (22 plates).

(14) Hébron, le Haram el-Khalîl, sépulture des Patriarches, by L.-H. Vincent, E. Mackay and F.-M. Abel, Leroux, Paris 1923 (28 plates).

(15) Emmaüs. Sa basilique et son histoire, by L.-H. Vincent and F.-M. Abel, Paris 1932 (27 plates).

(16) The story of certain expeditions, typically Mission en Arabie and Croisière sur la mer Morte, but also the articles in the Revue Biblique.

(17) For example the great syntheses illustrated with photographs of Jerusalem by Vincent and Abel, Jérusalem sous terre (1911), Jérusalem antique (1912), Jérusalem nouvelle (1914, 1926), Jérusalem de l’Ancien Testament (1954, 1956) works whose development took many years of work.

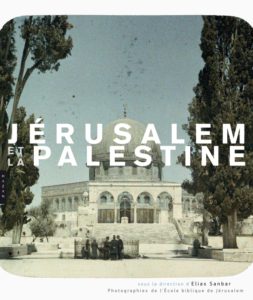

Le fr. Jean-Michel de Tarragon est en charge de la photothèque depuis de nombreuses années : le travail est colossal. Il est à l’École biblique depuis 1980, et fut membre et photographe de beaucoup d’expéditions archéologiques. Ce texte est tiré du livre Jérusalem et la Palestine, réalisé sous la direction d’Elias Sanbar, à partir du fonds photographique de l’École biblique, chez Hazan. En savoir plus sur notre photothèque.

Le fr. Jean-Michel de Tarragon est en charge de la photothèque depuis de nombreuses années : le travail est colossal. Il est à l’École biblique depuis 1980, et fut membre et photographe de beaucoup d’expéditions archéologiques. Ce texte est tiré du livre Jérusalem et la Palestine, réalisé sous la direction d’Elias Sanbar, à partir du fonds photographique de l’École biblique, chez Hazan. En savoir plus sur notre photothèque.

Father Marie-Joseph

Father Marie-Joseph